On 11 May 2023, the Bank of England announced that UK interest rates would rise for the 12th consecutive time. Rates are up from 4.25 per cent to 4.5 per cent. While this will massively impact the general public, how will the fintech industry be impacted by this 0.25 per cent rise?

The decision was made following seven of nine Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members voting in favour of raising interest rates, with the main reason provided for this being to stop inflation. The Bank of England has a goal to keep inflation at two per cent. However, according to the BBC, “prices are currently rising at more than five times that level”. Therefore, the decision to raise the base interest rate for the 12th consecutive time since December 2021 to an almost 15-year high was made.

When looking to understand the impact the Bank of England’s decision will have on fintech, you have to look at it from two angles. The immediate impact on the business, and the knock-on impact on the consumer.

Troubles in funding

One of the most notable ways in which fintechs will be impacted immediately will be when it comes to funding. Funds available a year ago simply are not there anymore. As a result, fintechs are struggling to gather enough to continue to innovate.

Commenting on this, Claire Trachet, CEO and founder of business advisory, Trachet said: “The current economic climate is presenting major challenges for companies with limited cash reserves. The Bank of England announcing an interest rate rise to 4.5 per cent, coupled with an inactive IPO market, means scaling businesses – predominantly in tech – are finding it increasingly difficult to secure funding.”

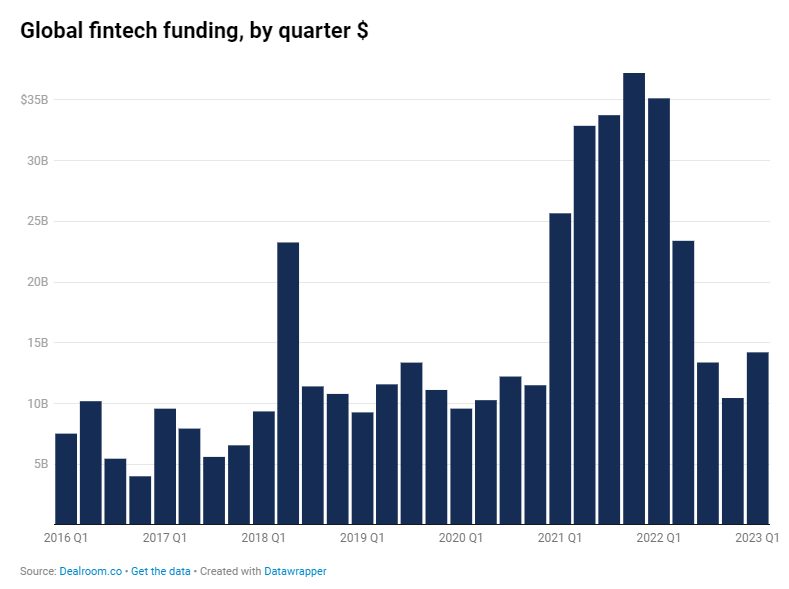

In Q1 2023, UK fintech startups raised a total of $595million. This was a drop of 65 per cent from total funding of $1.7billion in Q4 of 2022, according to Tacxn in its Geo Quarterly FinTech UK Report – Q1 2023. It was also 89 per cent lower than the funding of $5.5billion recorded in Q1 of 2022.

However, the UK was not alone in this drop. Putting this into perspective, according to Dealroom, global fintech funding dropped from $35billion to $14billion in the space of a year.

Higher costs mean cash can’t be retained

But why have we seen this drop? Adam Zoucha, MD EMEA FloQast, the accounting workflow automation solution, provides one possible reason. He said: “The increased cost of borrowing makes it harder to retain accessible cash. And, tightens the cash runway.”

Looking at the impact the hike will have, Zoucha said: “The financial resilience of organisations is being challenged from all sides. It is not just the cost of borrowing, wage-prices are spiralling and the cost of goods increasing. This hampers the ability of organisations to innovate and diversify.

“When resource is tight, the margin for financial error is finite. This puts the pressure on the finance team to ensure fiscal accuracy. Keeping cash flow in check, and performance on track, is crucial to survival. Yet, our research shows us that 17 per cent of UK organisations are still not confident in their month end numbers.”

Businesses need help to help consumers

Now more than ever, organisations need help to survive. However, the Prudential Regulation Authority‘s propsal to remove the SME supporting factor is arugably doing the opposite. This makes lending to small businesses less capital-intensive for banks. The Federation of Small Businesses national chair, Martin McTague, explained that removing this “would only make the lending situation more difficult for small businesses.” Research commissioned by SME lender Allica found that the proposed changes could result in a £44billion drop in SME lending.

Keeping the SME supporting factor would be a great step in the right direction to protecting the future of the UK’s economy (small businesses). McTangue further suggested another way would be: “The Government tackling late payment to free up cash for small firms in supply chains would also be a huge help. The value of wrongfully withheld payments is eroded for every day that funds are not released to supply chains.”

A last resort

Kevin Pratt, mortgage expert at Forbes Advisor also provided a few way in which the government could help fintechs and businesses through this interest hike. He said: “Hiking bank rate is a blunt instrument. However, the Bank of England has little else at its disposal as it tries to get inflation down from 10.1 per cent to its target of just two per cent.

“Perhaps other interventions are necessary from the government to help ease the pressure on UK plc, such as persuading energy suppliers to negotiate with their business customers to lower bills to affordable levels, and targeting VAT relief at the most beleaguered sectors, such as hospitality.

Pratt further explained how a lack of help and lending to SMEs would ultimately just lead to a higher price for consumers: “Businesses in particular will be growing weary of hearing the Bank of England say it is using rate increases to cool the economy by making it more expensive for them to borrow.

“As the Federation of Small Businesses said on Tuesday, tens of thousands of firms are on the brink of closure because of crippling energy bills. Those that survive will only do so by passing on their increased costs to their customers. How does raising the cost of borrowing tackle that inflationary stimulus?”

Where to next?

As difficult a time as this is for fintechs and their consumers, organisations must adapt to the changes. For Andrew Boyajian, head of variable recurring payments at Tink, the open banking platform, one solution that will help see fintechs through to the light at the end of the tunnel is variable recurring payments. He said: “Finding ways to financially support the UK’s consumers is crucial. Leaning on fintech developments such as open banking-powered variable recurring payments (VRPs), may well form part of the answer. It could play a role in helping people navigate this financially challenging period.

“For example, VRPs give consumers more control and visibility of their monthly outgoings. This is in addition to greater flexibility over when and how often a recurring payment will occur. Indeed, VRPs are also enabling users to review and change/ cancel any subscription in a few clicks through their bank app, ensuring maximum transparency and control for consumers.

“In the current challenging economic climate, unlocking new ways to help consumers manage their finances should be at the top of the industry’s agenda — particularly now as people look to navigate the associated financial impact that rising interest rates may bring.”

Was the interest hike actually necessary?

Not everyone in the industry was in agreement that the interest hike was necessary. While some believed it to be the only way to counter inflation, others thought it to be an overcorrection. Trevor Williams, chair of the institute of economic affairs’ Shadow Monetary Policy Committee and former chief econonmist at Lloyds Bank, said: “The Bank of England helped create the inflation problem. Then it said there wasn’t a problem. Then it called it ‘temporary’, and now it runs a significant risk of overcorrecting.

“Just as the Bank of England failed to identify inflationary pressures at the tail end of the covid-19 pandemic, they may be once again focusing too much on present inflation rather than long run trends. The sharp reduction in the money supply points towards inflation coming down quickly over the coming two years. The UK’s sluggish economic growth, easing supply chain pressures and a series of recent bank failures also point against the need for further rate rises.

“Inflation could still dip to around one per cent over the next two to three years and even after adjusting for the Bank’s revised forecast suggesting stronger growth, it is expected to undershoot the two per cent target. This trajectory indicates interest rates need not go up any further.”

The UK must endure another month of the high interest rates before the BoE’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meets on 22 June to revise the UK interest rate.